Water

In the Wake of the 'Dulcibella'

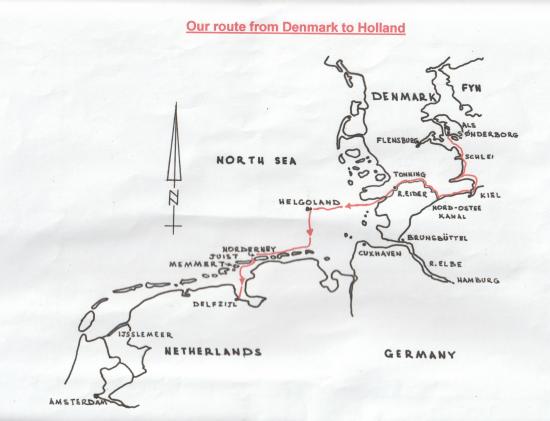

In the wake of the 'Dulcibella', or how we were lead to a shoal water challenge.

Having just re-read the wonderful sailing classic The Riddle of the Sands, written in 1903, we realised that we had, without intent, been sailing to many of the places that Davies and Carruthers had visited.

While R.M. Bowker, in his historical postscript to the 1976 reprint, debates the relative proportion of truth and fiction, no one debates the reality of the sailing so vividly described in this wonderful book.

We have kept our Vancouver 32 "Juliet" in the Baltic for two seasons and in 2000/2001 overwintered in Augustenborg, Denmark, We were reminded that this area of Schleswig Holstein has been much fought over and at the time the book was written was part of Germany. Before laying up we had sailed into the Flensburg Fjord, although not to the anchorage that Davies used, and visited "quiet old Sonderborg, with its broad eaved houses and carved woodwork - Danish to the core under its Teutonic veneer".

These old charms were not quite so evident, and "the lumbering pontoon bridge" which opened to give Dulcibella passage through the busy Als Sund is now a modern affair with a large screen showing how many minutes you must wait until the next opening. The Dybbol heights on the opposite shore were described in the book as "of bloody memory, scene of the last desperate stand of the Danes in '64, ere the Prussians wrested the two fair provinces from them.".

It was our first visit to Denmark and when we returned to the boat in May we spent a month of very enjoyable cruising in Danish waters before heading homewards to our Cornish mooring. We went into Schlei fjord (now German territory). Dulcibella had been here in October on the pretext of searching for some duck shooting. The entrance to this long fjord is still much as he described "only 80 yards wide, though it leads to a fjord 30 miles long. The channel grudgingly disclosed itself, stealing between marshes and meadows...". The entrance is now easy to spot as it has a large lighthouse and some buoyage, as well as ferry boats and plenty of yachts coming and going. We were too early in the season for migratory wildfowl but there was a large and lovely nature reserve of reed beds, marsh and sand dunes just inside the entrance, where I enjoyed a long walk and saw many birds.

We next picked up Dulcibella's track when we passed Bulk Point lighthouse at the entrance of the Kielder Fjord on the way to the canal, where the "colossal gates of the Holtenau lock opened with ponderous majesty and our tiny hull was lost in the void of a lock designed to float the largest battleship". At the time he wrote this the Canal was new and named Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. The lock is still very large as the canal carries much commercial traffic but the gates were not the original, but they were still an impressive sight as they closed on our last glimpse of the Baltic and we felt quite small.

We had no particular wish to transit the dull and busy canal and exit at Brunsbuttel. Erskine Childers' description of the Elbe from Brunsbuttel is still accurate "It is fifteen miles to the mouth: drab dreary miles, the dullest reaches of the lower Thames. The tide as it gathered strength swept us with a force attested by the speed with which buoys came in sight, nodded above and passed, each boiling in its eddy of dirty foam."

We planned to leave the canal, via the short Gieselan canal into the beautiful and peaceful River Eider. We stopped on the way at the lovely town of Friedrichstadt, which was a Dutch settlement of the 17th century.

We stayed for a day in the lovely town of Tonning, near the mouth of the river. The harbour is mentioned in the book when Davies had sailed up the river. We were allocated a place by the footbridge where we just remained afloat, although most of the harbour dries. "Juliet", with her red gunwale stripe, can be see in the foreground of the picture.

In Dulcibella's time the town suffered many devastating tidal and storm floods. It is now protected from the sea by a tidal barrage and lock, reached by a seven mile winding channel, through sandbanks where we saw many basking seals. Once out to sea the next day, carrying the full ebb tide, the route was well buoyed but tortuous through many sandbanks where the sea was breaking - certainly not an area to be caught in bad weather. We sailed out to the island of Helgoland. It was ugly and much visited by ferries on shopping trips from neighbouring countries as it has a duty free status. It was, however, a useful staging post for us with the tide and weather planning.

We stayed here overnight, and thence to the German Frisian island of Norderney. These low lying sand islands are still unspoilt, though not so lightly inhabited as in the days of the book. The beaches were popular but the interior was empty. We had a lovely cycle ride on a sandy track out to the lighthouse.

The vast Waddenzee, behind the islands, is a maze of drying ground that was daunting to us Cornish sailors used to plenty of water under the keel. The Dutch, however, are used to such waters and have a toast "May there always be a cup full of water under your keel". In the book Davies says to Carruthers (indicating the area of drying sands on the chart) "The chart may look simple to you ('simple'! I thought) but at half flood all those are covered; the islands and coasts are scarcely visible, they are so low, and everything looks the same."

"Juliet" draws 1.5 metres and at the beginning of our trip, we had no intention of messing with the watershed routes! Davies loved the challenge of shoal draft navigation but his centreboard boat was ideally suited, as he said "that's where our shallow draught and flat bottom come in - we could go anywhere and it didn't matter running aground. Perfect for that sort of work." However, we gradually became beguiled with the notion of following the route through the sands that Davies and Carruthers had rowed in the fog from Norderney, via the Memmert Balje.

I cannot better Davies' description when he explained the concept of a watershed to a perplexed Carruthers as they were studying the chart - "A big sand such as this is like a range of hills dividing two plains it is never dead flat, there is always one ridge where it is highest; at low water it is generally dry there, and it gradually deepens as it gets nearer the sea on either side. Now at high tide, when the whole sand is covered, the water can travel where it likes; but directly the ebb sets in the water falls away on each side, and the channel becomes two rivers flowing in opposite directions from the centre. When the flood begins the channel is fed by two currents flowing to the centre and meeting in the middle".

Unless you have a boat that can safely take the ground if you make a mistake, it is essential that you navigate these waters with the most up to date chart as the sands are constantly shifting. These are printed in March each year. The sandy islands also change. The size and shape of Memmert is substantially different from when the book was written in 1903.

We checked and double checked our calculations and left harbour at Norderney at 08.05, and the whole of the 3 hour passage before we were back into deep water went without a hitch. The marks were good with the withies in the crucial places being very closely spaced. They looked like small birch trees growing out of the vast vista of open water, and the system is for the twigs to point upwards for port hand marks and to be bound to point downwards for a starboard mark, and often they also had red or green tape around the stem. On the narrow part of this channel there were just withies on our starboard side and we had to pass them very close to keep the best water.

At the watershed we had 0.3 m under the keel. Although we were expecting it, it was still very strange to have the noticeable tidal stream with us one minute and against us a few minutes later!

We had not quite said goodbye to the ghost of Dulcibella as we sailed right through the canals of Holland and enjoyed the Ijsselmeer. When Davies sailed here it was still open to the sea and he describes the "Zuyder Zee shut in by the islands of Texel and Vlieland". He also visited Amsterdam, as we did.

The reading, and re-reading of this classic book has added a new enjoyment to this year's sailing

© Margaret Honey, January 2026, All rights reserved

This article is protected by copyright - please contact editor@landulph.org.uk if you want to use it.

All the quotations in this article are from ‘the Riddle of the Sands’ by Erskine Childers. This novel, beloved by many, was also made into an excellent film. If you haven’t read the book, it’s highly recommended. [Ed]